Protests against compulsory veiling are the latest examples of female resistance in the Islamic country, says Middle East expert Claudia Yaghoobi.

Emily Padula, The Well, Friday, October 28th, 2022

Protestors take part in demonstration in front of the Iranian embassy in Brussels, Belgium following the death of Mahsa Jina Amini (pictured above). (Shutterstock)

As a wave of protests stemming from the death of a 22-year-old Iranian woman enters its second month, demonstrations have spread worldwide.

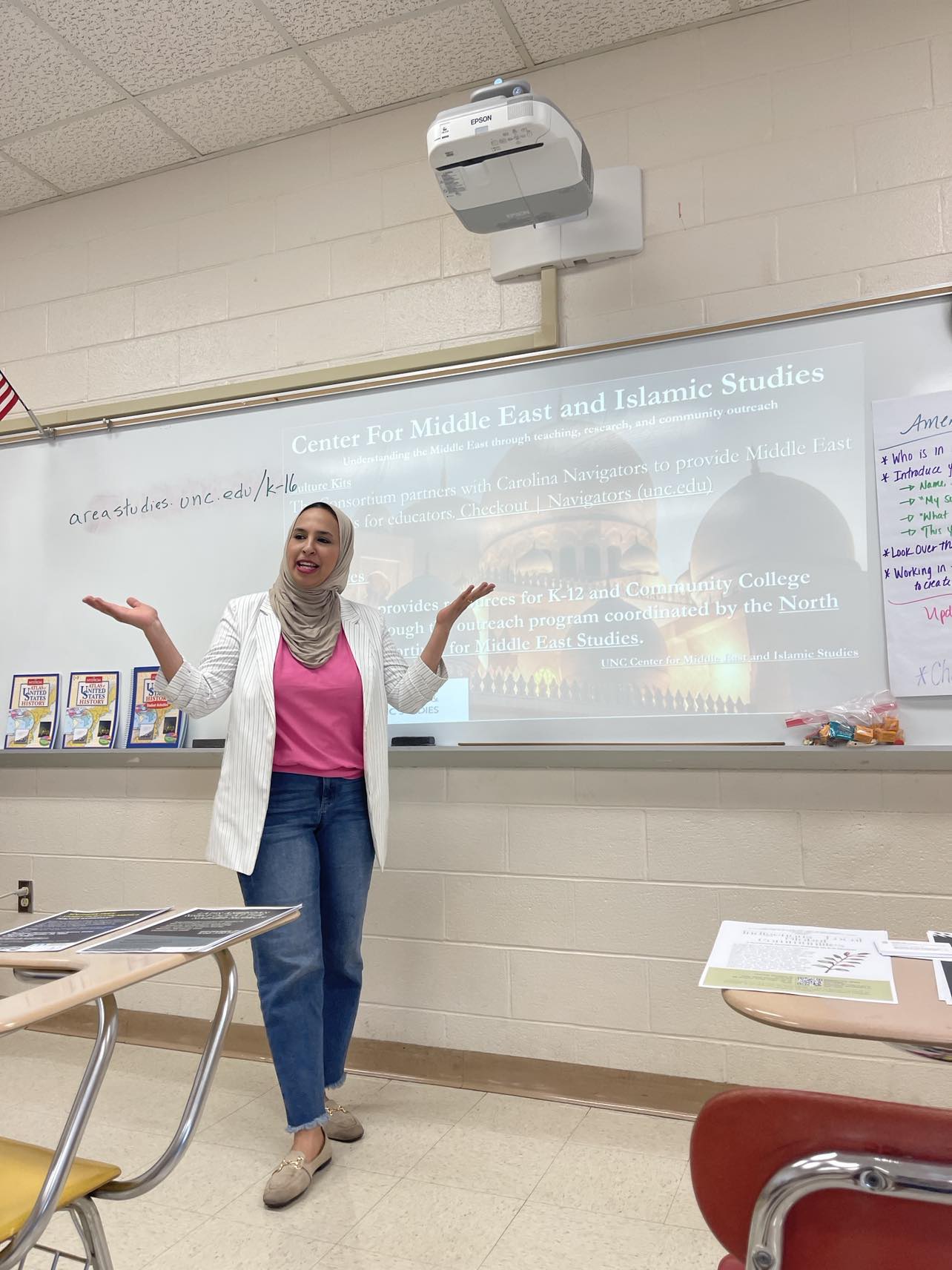

Claudia Yaghoobi, an Iranian Armenian American and the director of the Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies, answered questions from The Well about what led to the historic protests, how the fallout compares to previous conflicts and more. Yaghoobi is also the Roshan Institute Associate Professor in Persian Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences’ department of Asian and Middle Eastern studies.

What sparked the protests and who is protesting?

In September 2022, protests broke out spontaneously across the country after images appeared on social media of 22-year-old Mahsa Jina Amini, an Iranian Kurdish woman, unconscious on a hospital bed. She was declared dead on Sept. 16, three days after being arrested on a Tehran street by the morality police.

The Kurdish phrase “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (“Woman, Life, Freedom”), derived from years of Kurdish resistance and activism, became the slogan of this moment. Amini’s parents made a conscious decision to hold her funeral publicly even though they had been told not to. This incited protests in Saghez during the funeral when women began taking off their veils and cutting their hair. Thereafter, in almost all cities of Iran protests arose and women began cutting their hair and burning their hijabs in solidarity. The protests, or what’s been called feminist social revolution, continue to this day, as we are in the sixth week.

The protests are different in a few aspects from other protests or revolutions. For instance, they are leaderless, and people from various socio-economic gender, sexual, ethno-religious backgrounds are united. This is no longer the revolution of the educated urban middle class or upper middle class. This is a movement where all sectors of the society — Kurdish and Baluch people, men and women, the trans and queer communities, urban and rural — have come together. Mahsa Jina Amini was an ordinary woman from Saghez visiting Tehran with her family. She was not a dissident or anti-veiling activist. So, this could be anyone. And that’s why she’s united everyone.

What do the protestors want?

A few weeks ago, Yaghoobi shaved her hair in solidarity with Iranian women.

Their common demand is not simply to end the morality police or veiling laws but to end the theocratic authoritarian regime. This is a historic moment in Iran’s history. However, it is not a moment divorced from other moments in Iran’s history, so it is important to place it in the historical context of its birth and evolution. It is crucial to also understand the multi-layered nuances to avoid reductionism.

Mahsa Jina Amini’s alleged improper veiling is testimony to the fact that even though the Islamic Republic subjects women to its oppressive regulations, it also paradoxically fears women as possessing the power to disrupt or establish social stability.

How does this unrest compare to previous unrest?

While the recent protests against compulsory veiling in Iran mark another crucial historic moment in the history of Iranian women’s resistance, it is important to recognize that Iranian women have struggled for the right to unveil (or veil) for almost 170 years.

The current moment is a testimony to how successive Iranian regimes have utilized veiling practices to exercise authority over women by denying them the right to their bodily autonomy and the right to appear in public. It began during the Qajar Era (1789-1925), when the hijab was a social class marker, and continued with the 1852 execution of Tahirih Qurrat al-‘Ayn, a poet, women’s right activist and theologian of Babi faith; the 1936 police enforced unveiling of Reza Shah Pahlavi; the 1970s voluntary veiling of women against the Western imperialism; and the 1979 compulsory veiling decree of Ayatollah Khomeini.

Focusing on the past 43 years, since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, we can see that Iranian women have continued asserting themselves in public spaces designed to exclude them, and they have faced targeted violence and media narratives aimed at disqualifying them from accessing public spaces.

After the 1979 revolution, women’s show of force and criticism of the revolutionary regime heightened hostility toward feminists and secular women in general and set in motion the process of their marginalization through various policies and increased public harassment. The regime opened the sociopolitical arenas to conservative women. Considerable resources were used to put together a so-called morality police to enforce these new dictates. In the aftermath of the revolution, a purification campaign started to eradicate urban professional women and feminists from the public, who, according to Khomeini, were “corrupt manifestations of the monarchical regime and the West.”

In 1993, Homa Darabi, a pediatric specialist and psychologist, self-immolated in Tehran’s crowded Tajrish square to protest the wearing of the compulsory hijab at workplace. Darabi’s public act of dissent alludes to the dominant discourses concerning how the public/private divide impacts women’s lives.

Exclusions of women from public spaces, as maintained through the veil in Iran after the Islamic Revolution, deny women the right to participate in public conversations regarding democracy. However, often women such as Darabi have resisted this exclusion and have endeavored to reclaim public spaces by their physical presence and radical acts in crowded public spaces. The presence of “wrong” bodies in public spaces is, however, a direct challenge to the structural power of institutions that dictate women’s behavior, dress and public demeanor. Since bodies are socially constructed and are intertwined with the spaces they occupy, Darabi’s self-immolation in one of Tehran’s most populated spaces can be viewed as a final rejection of the conditions advanced by the state, and her tragic reclaiming of autonomy over her body. In this process, the question of gender and sexuality grew increasingly politicized in Iran.

In the 2010s, the internet and social media became tools in women’s anti-compulsory veiling activism. Campaigns such as “No to Compulsory Hijab” in 2013, “We’ll vote unveiled” in 2015, “My Stealthy Freedom” in 2015 and the “White Wednesdays” of 2017 are a few examples. On Dec. 27, 2017, Vida Movahed climbed onto a utility box in Enghelab (Revolution) Street, tied her white headscarf to a stick and waved it to the crowd, transforming what was a hijab into a flag. She was immediately arrested. A month later, she was released temporarily on bail. However, #girlsofrevolutionstreet was born out of this moment.

In July 2022, Ebrahim Raisi, the current president, signed a decree to enforce stricter hijab laws, which included threats to fire women employees. All the while the state forces began harassing and arresting women, particularly women’s rights activists, for their improperly veiled or without veil social media profile photos.

Have the protests spread outside Iran?

Over the past five weeks, the Iranian Americans and Iranians in diaspora all over the world have endeavored to be the voice of Iranians fighting inside the country. There have been academic panels, teach-in sessions, vigils and moments of silence in so many different universities, along with marches and protests. On Oct. 1, there were organized protests in 150 cities across the world. For example, 50,000 people attended one in Toronto.

At Carolina, we had “A Moment of Collective Silence and Solidarity” on Sept. 29, a panel of scholars on Oct. 3 and a teach-in on Oct. 11. There have been protests in Raleigh and Durham on several Saturdays as well.

Posted from Campus News