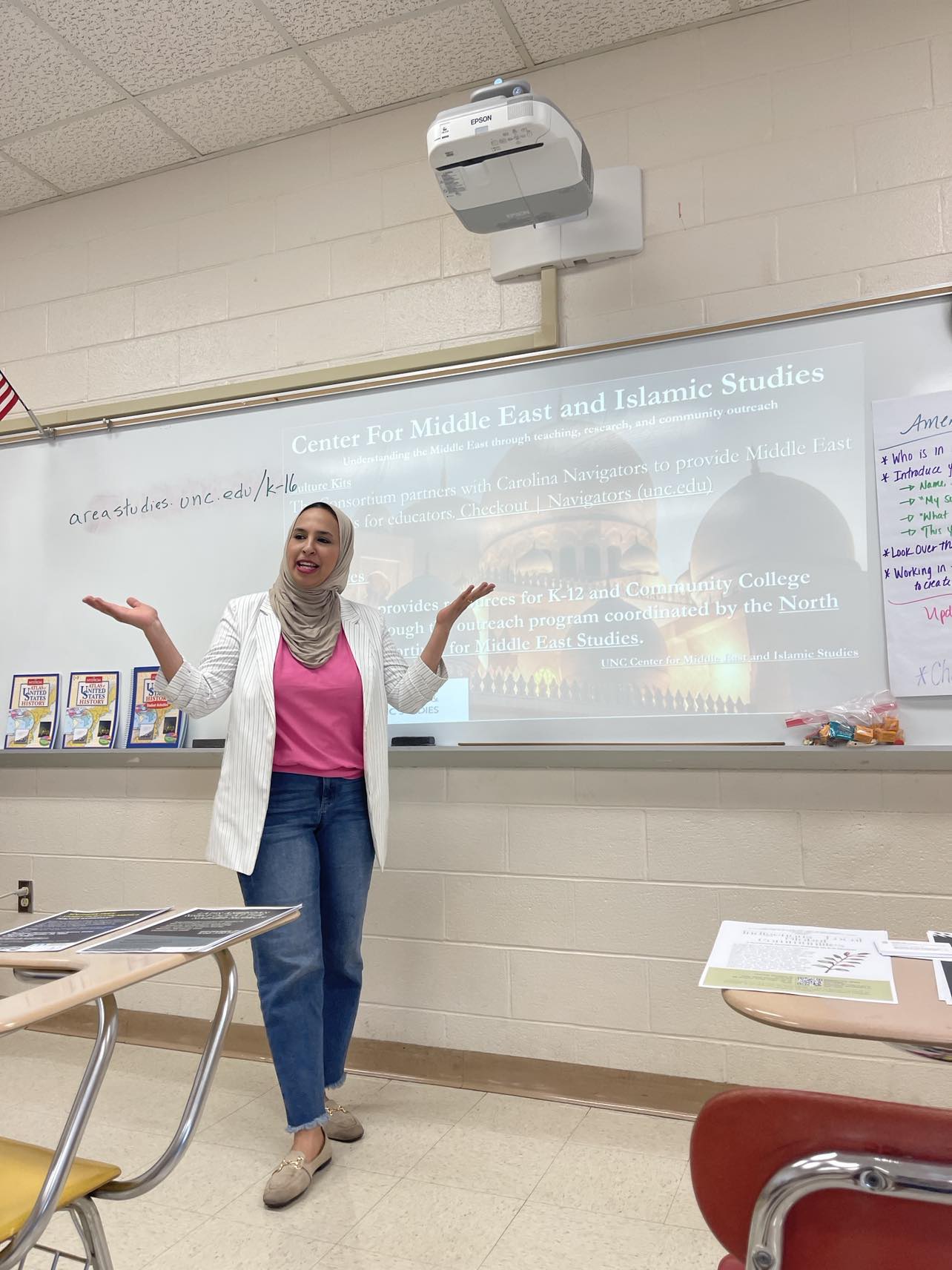

Overview and Purpose

On March 22-24, 2019, the Duke-UNC Consortium for Middle East Studies held a conference on “Conflict Over Gaza: People, Politics, and Possibilities.”

For the past eight years, the Duke-UNC Consortium for Middle East Studies has held an annual conference on an important topic in the contemporary Middle East. Given conditions in the region, these topics can be controversial, and the goal of these conferences is to provide sober, scholarly perspectives on difficult issues. The goal of this year’s conference was to bring together experts on human realities in Gaza, giving participants a deeper understanding of the context of these realities and exploring opportunities to improve the lives of Gazans. The conference also highlighted Gazan culture–music, films, food, and art–to emphasize the daily experience of the two million people who live in the Gaza Strip.

This may have been the first scholarly conference in the United States specifically focused on the people of Gaza, the small territory on the Mediterranean Sea that has experienced more than a decade of authoritarian rule and sealed borders that limit the flow of people and goods. The ongoing humanitarian crisis in Gaza is the product of a political crisis: with ongoing hostilities between Hamas, the Islamist movement that rules Gaza and attacks Israeli civilians as part of its revolutionary campaign to establish an Islamic state; Israel, which controls Gaza’s coastal waters, airspace, and five-sixths of Gaza’s land borders; Fatah, the Palestinian secular-nationalist movement that governs the West Bank; and Egypt, which controls Gaza’s southern border. The people of Gaza face complex problems with few solutions in sight.

The conflict over Gaza raises difficult humanitarian and political issues. As scholars who study the Middle East, the conference organizers believe that these important issues should not be avoided just because they are controversial. Indeed, their controversial nature is part of what makes them important for scholarly study and debate. At the same time, the conference organizers took care to approach this controversial subject in a responsible way that incorporated expertise and multiple scholarly perspectives.

The first evening featured a musical performance by Tamer Nafar, a Palestinian hip-hop artist and human rights activist who lives in Israel. The second day consisted of five panels, each with two featured speakers and faculty moderators. The third day involved a film festival with discussions by film scholars. The conference also offered refreshments prepared according to recipes from Gaza, a photojournalism display, and a small art exhibit. The conference program can be found online.

Conference Organization

Conference organizers selected ten panelists with first-hand expertise on the situation in Gaza and multiple perspectives and backgrounds. Half of the panelists were Palestinian, and half were not.

On the economy, the conference included the world’s foremost expert on the economy in Gaza.

On health conditions, the conference included the director of the Gaza Community Mental Health Programme, who spoke and answered questions via internet audio/video.

On humanitarian aid, the conference included two employees of humanitarian aid organizations in Gaza. One works for a nonprofit organization based in the United States; the other works for a United Nations agency.

On the implications of the limited mobility of the people of Gaza, the conference included the director of the leading Israeli organization that specializes on this subject.

On the culture of Gaza, the conference included the author of The Gaza Kitchen, whose recipes were used by a local caterer for refreshments at the conference.

On the politics of Gaza, the conference included four specialists with a variety of forms of expertise:

- An expert from a conservative think-tank in Washington, DC.

- A former U.S. foreign service officer who served in Israel.

- A political scientist who served as president of the Middle East Studies Association and specializes in the study of Islamist movements, including Hamas.

- The former director of the Carter Center’s field office in Jerusalem.

In addition to these panels, the conference included a film series, “Gaza on Screen,” which was curated to invite reflection on both the history of filmmaking in Gaza and a variety of cinematic engagements with the experiences and circumstances of the people of Gaza.

All of the panels and films were moderated by Middle East studies specialists on the faculty of Duke and UNC.

The conference space also featured photographs taken by Gazan photojournalist Mohammed Zaanoun, whose work has appeared in many international news outlets. His images present scenes of daily life in Gaza, as well as moments of political upheaval.

The conference organizers initially wanted to include a musical performance by an artist from Gaza, but found travel arrangements too daunting – a reflection of the limited mobility of the people of Gaza, which was one of the subjects the conference sought to study. Instead, the conference included a musical performance by Tamer Nafar, a major Palestinian performing artist and human rights activist, who lives in Israel and is frequently profiled and covered by major news organizations, most recently by The New York Times. Nafar was among the first Arab artists to explore and globalize Arab hip-hop music, and his musical work has been the subject of many studies in the field of musicology. In addition, Nafar performs regularly with Jewish Israeli musicians and advocates peaceful solutions to the humanitarian and political problems of the region. Unfortunately, Nafar’s performance at the conference was marred by hurtful remarks he made at the beginning of one song, which the Duke-UNC Consortium for Middle East Studies apologizes for and rejects.

Conference Panels

The conference panels provided thoughtful, evidence-based analyses of the experience of life in Gaza. Many participants also discussed the actions of political parties – including Hamas, Fatah, Israel, and Egypt, as well as their international supporters — that have contributed to the ongoing humanitarian and political crisis.

The first panel focused on economic and social issues in Gaza. Sara Roy of Harvard University spoke about the “de-development” of Gaza caused by the ongoing political stalemate and limited access to outside markets or job opportunities. Laila El Haddad, author of The Gaza Kitchen, described challenges of everyday life in Gaza. She also discussed the cultural heritage of Gaza, a region that included numerous villages outside of the current ceasefire lines. Gaza’s location as a historical crossroads in the eastern Mediterranean positioned it to construct its own distinctive cuisine, drawing on flavors and styles from around the region.

The second panel focused on humanitarian and health conditions in Gaza. Hani Almadhoun of the U.S.-based nonprofit organization, American Near East Refugee Aid, spoke about the need for humanitarian assistance in Gaza and the practical challenges of aid delivery. In particular, Almadhoun described the difficult process of accessing Gaza via Egypt. Yasser Abu Jamei, director of the Gaza Community Mental Health Programme, spoke about the prevalence of mental health issues in a population that feels under siege. He joined the conference via Skype from Gaza, and his video connection was poor and stalled frequently because of Gaza’s limited broadband internet access, another feature of the ongoing challenges that the people of Gaza face.

The third panel focused on the limited mobility of the people of Gaza, with presentations by a Jewish Israeli expert on the subject and a United Nations employee from Gaza. Tania Hary, director of the Israeli legal center Gisha, which specializes on the freedom of movement, spoke about Israeli restrictions on the portion of land that borders of Gaza. She described the security rationale for these restrictions, and her organization’s legal challenges to Israeli policies. Mohammed Eid, an employee of the United Nations relief organization in Gaza who is currently on a fellowship for peace and conflict resolution at UNC, spoke about his difficult experience leaving Gaza to take up his fellowship, including long delays in processing approvals, anxieties at the final Hamas checkpoint, and brief detention by Israeli authorities.

The fourth panel focused on Hamas and Fatah, the two dominant Palestinian political organizations. Nathan Brown, professor of political science and former president of the Middle East Studies Association, talked about the authoritarian rule of these organizations in Gaza and the West Bank, respectively, and the rivalry between the two. He noted that Hamas, though it is supported by only a minority of the Palestinian population, has been more effective than Fatah in transitioning to a younger generation of leadership. Nathan Stock, former director of the Carter Center’s field office in Jerusalem, talked about the difficulties in bringing together Hamas and Fatah for negotiation and reconciliation with one another and with Israel. He described moments in recent years when it appeared that compromises might be struck that would allow some relaxation of tensions and alleviation of security concerns, and how these opportunities for progress have repeatedly been undermined by political circumstances on all sides.

The final panel focused on Gaza’s relationship with Israel, Egypt, and the United States, with panelists representing different perspectives. Lara Friedman, a former U.S. foreign service officer who now heads the Foundation for Middle East Peace, spoke about the state of dependency that the people of Gaza find themselves in, given their reliance on neighboring states for the necessities of life. Ghaith al-Omari, an expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, spoke about the security concerns of Israel, given Hamas’s attacks on Israeli civilians, and stressed the need for all sides to avoid escalations of conflict.

All of the panels took questions from the audience, including some questions that were quite pointed. Audience members were asked to make their questions brief, to save time for others, and to refrain from making their own statements.

Contrary to misrepresentations that appeared online, the conference did not criticize Israeli policies exclusively. Panelists scrutinized the role of all sides in the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, including Hamas. One panel was devoted specifically to a discussion of Hamas.

The conference organizers thank the panelists for their analyses of conditions in Gaza, in keeping with the conference’s intention to increase understanding of this difficult situation in a responsible way.

Film Festival

The film festival, “Gaza on Screen,” began with a series of short films selected to introduce audiences to changes in filmmaking in Gaza since the 1970s, including representations of violence in different ways across varied historical and political contexts.

The festival then screened three feature-length films: an experimental work by acclaimed artist Basma Alsharif that explores the possibility of hope; a fictional film set within a beauty salon in Gaza; and a documentary that traced the story of one family’s experience during the 2008-2009 war in Gaza and its aftermath. Each screening was followed by comments by a specialist from the UNC faculty and discussion with the audience.

While conversations were wide-ranging and fluid, certain themes rose to the top. Scholars and audience members noted both the differences in filmmaking practices over time and the longstanding nature of the challenges that Gazans face, including lack of mobility, overcrowding, and economic deprivation. Moderators led informative discussions about the films’ use of symbolism, gender issues, and the traumatic effects of violence. The day of screenings offered viewers an in-depth and nuanced view of life in Gaza and the various ways in which that life has been represented on screen.

Musical Performance

Tamer Nafar performed a series of his hip-hop songs in Arabic, Hebrew, and English that spoke to the challenges and everyday experiences of Palestinians, interspersed with spoken reflections and commentary in English. These songs addressed human rights, LGBTQ and women’s rights, love songs, and reflections about his late father, whose music collection consisted of two albums: one by an imam and one by the Beatles.

His performance was marred by comments he made while introducing his song, “Mama, I Fell in Love with a Jew.” This song was released in Israel two years ago. The Israeli newspaper Haaretz described it as an effort to “inject some humor into politics of coexistence between Jews and Arabs in Israel.” The song describes an unexpected romance with a Jewish woman under divisive sociopolitical conditions. The lyrics can be found online.

Regrettably, in introducing the song, Nafar described it as “my anti-Semitic song.” As Nafar began the chorus of the song, he encouraged the audience to sing along, saying, “I need your help. I can’t be anti-Semitic alone, try it with me together.” The audience did not stand and cheer for anti-Semitism, contrary to appearances in a video that circulated online. The cheering was for a different part of the concert – this is clear from the video itself, which shows different lighting and a different musical beat for the cheering and for Nafar’s comments.

While we cannot speak for the performer nor confirm his intentions, he provided the following comments to the Israeli news outlet Ynet on the incident (translation from Hebrew):

All my life I fight against all types of racism, including anti-Semitism of course. The cynical use of the term anti-Semitism against human rights activists hurts the struggle against true anti-Semitism. This is an ironic song that was created by a mixed [Arab/Jewish] team and is played in mixed weddings and the Israeli radio. Before the song, I laugh at the cynical use of the term anti-Semitism by racists to silence human rights activists like Angela Davis and myself.

Regardless of the performer’s intentions, the conference organizers believe that his comments were inappropriate and hurtful and not representative of the purpose of the conference. The Duke-UNC Consortium for Middle East Studies rejects anti-Semitism and all forms of racism and bias and apologizes for the hurt these remarks have caused, especially in the context of recent anti-Semitic incidents in the United States.

As inappropriate as Nafar’s comments were, his comments were protected by North Carolina’s Restore/Preserve Campus Free Speech Act of 2017, which says that University of North Carolina campuses may not “shield individuals from speech protected by the First Amendment, including, without limitation, ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive.”

Despite this protection, we do not wish to defend the conference solely on the grounds of academic freedom and freedom of speech, as important as they are. Rather, we believe the conference on “Conflict Over Gaza” was a conscientious, scholarly treatment of a significant humanitarian crisis. This conference was one event out of the hundreds that the Duke-UNC Consortium for Middle East Studies organizes, co-sponsors, and promotes each year, expressing diverse viewpoints and experiences. We are saddened that this scholarly event was marred by any association with anti-Semitism.