Scholars from the department of African, African American and diaspora studies and a University Libraries digitization specialist traveled to Senegal and Mali to preserve and digitize 6,000 pages of handwritten Islamic manuscripts.

Samba Camara sits in his office with a camera in the foreground and his computer in the background.

Samba Camara and his colleagues digitized 6,000 pages of important Islamic manuscripts. On his computer screen is a photo of the young Islamic leader Al Hajj Umar Taal taken on his visit to Egypt. (photo by Donn Young)

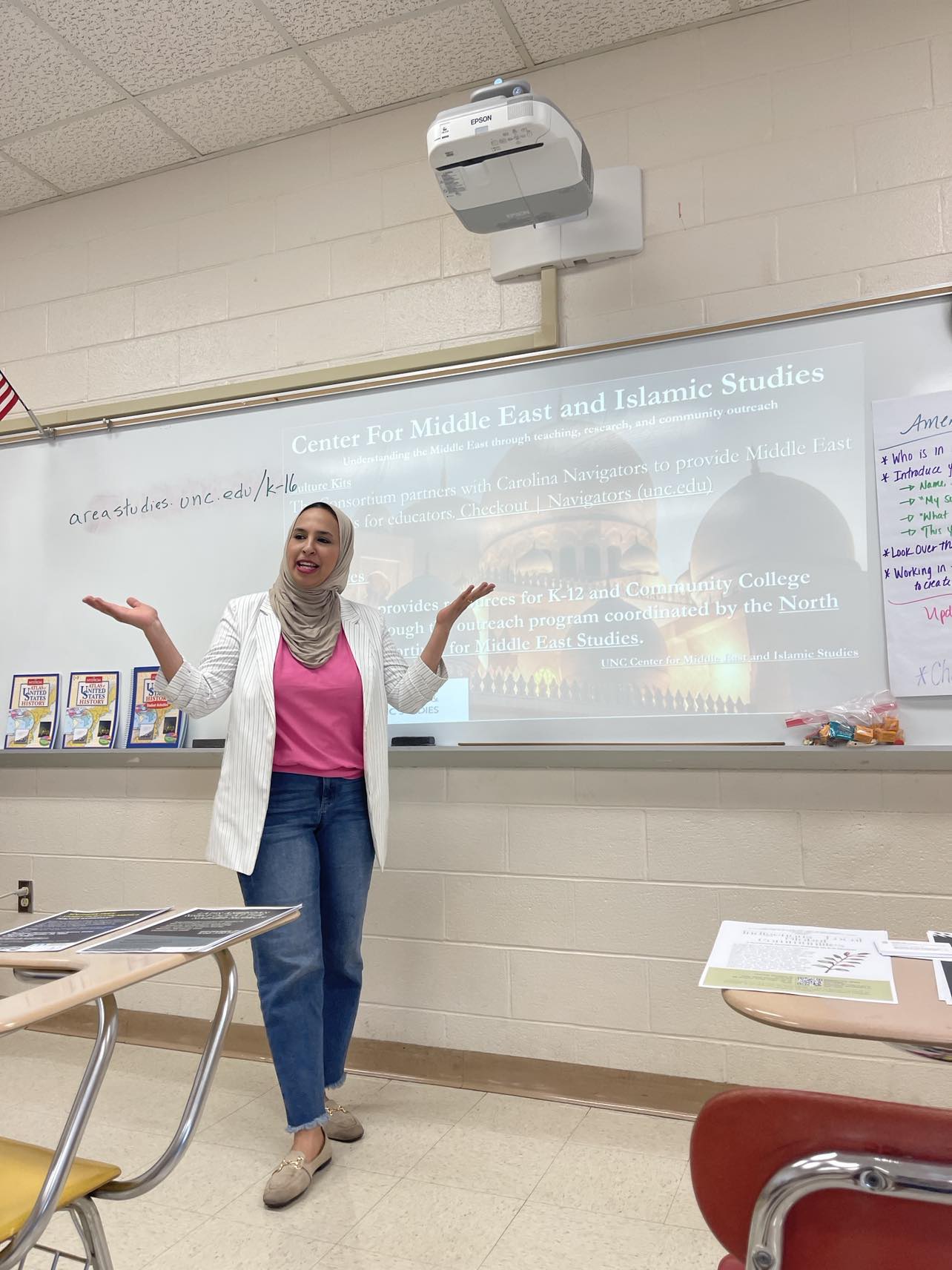

In the summer of 2018, Samba Camara traveled to his native Senegal, to the homeland of the the Haalpulaar people in the semidesert region known as Futa Toro.

A teaching assistant professor in the department of African, African American and diaspora studies in UNC’s College of Arts & Sciences, Camara investigates the influence of Islam on West African popular music.

“We were talking about this Pulaar poetry I grew up hearing, and a conversation emerged about preserving this poetry, which is often held in family libraries,” Camara said. “I contacted a colleague of mine at Boston University, who encouraged me to apply for a digitization grant to not only collect and preserve this poetry but to make it available to a larger audience.”

Pulaar is a Fula/Fulani language. It is the first language of millions of people (known as Haalpulaar) throughout West Africa and is a national language in countries such as Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, Guinea and Mali.

Camara partnered with his AAAD colleague, teaching associate professor Mohamed Mwamzandi, and University Libraries’ digitization support specialist Kerry Bannen on the project. Mwamzandi specializes in languages and linguistics and conducts research on African languages and literatures. The team received a grant in 2019 from the British Library’s Endangered Archives Program to digitize manuscripts written in Arabic and Pulaar by some of the most influential Haalpulaar Islamic scholars of the late 19th- and 20th centuries.

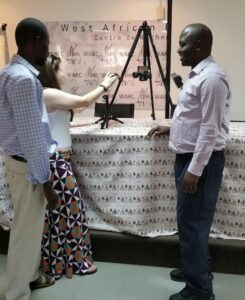

A team of scholars works with cameras and a laptop to digitize manuscripts pages.

A shooting session at the West African Research Center. From left to right: Mohamed Mwamzandi, Mountaga Ba, Kerry Bannen and Samba Camara.

The team members focused their preservation efforts on Islamic authors affiliated with the West African branch of the Tijaniyya Muslim Brotherhood pioneered by Al Hajj Umar Taal (1796-1864).

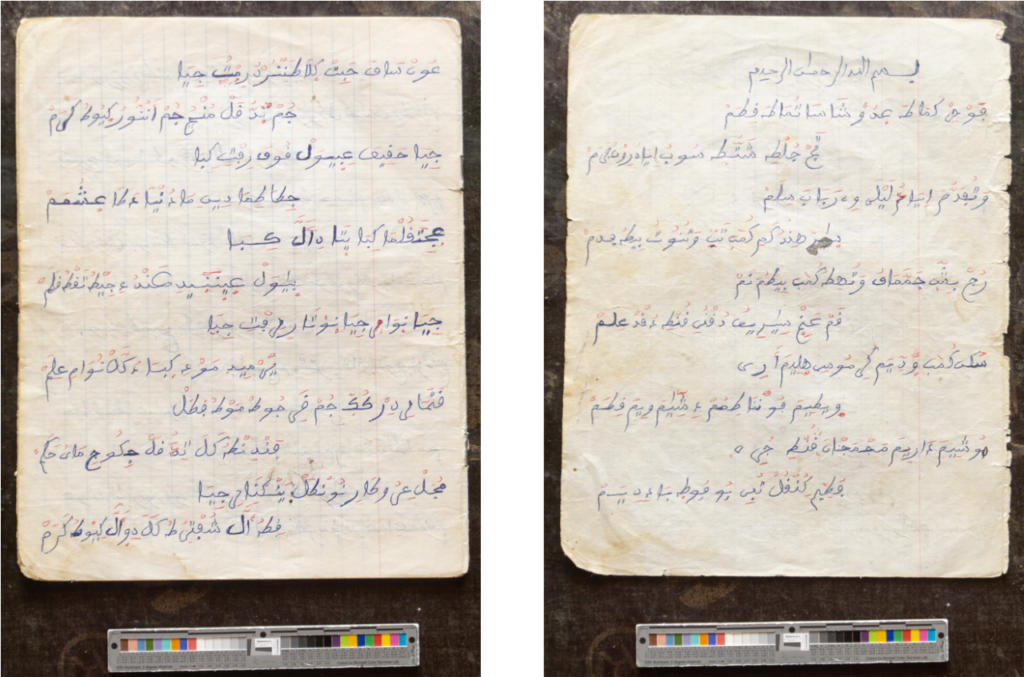

The Haalpulaar people were among the first Senegalese to widely embrace Islam. Haalpulaar scholars wrote Islamic manuscripts in Arabic, but also used the Arabic script to write poetry in the local language, a writing system known as Ajamī. Today, Arabic and Pulaar manuscripts are held in family libraries, while Taal’s original library still sits in French libraries since its colonial confiscation in 1890. Most of the manuscripts in Arabic are at the Taal family’s main library in Dakar, the capital of Senegal.

Camara said the body of work produced by the Haalpulaar is a bit of an untold story: “It became important to prove that this poetry existed and that it actually predated many of the manuscripts that we boast about in Senegal.”

Many of the manuscripts are fragile.

Digitized Pulaar poetry from the collection of Mountaga Ba.

“They were written using either a locally made ink called Daha or in pen, and were more vulnerable to being damaged by water, fire, termites, mold or just wear and tear,” said Mwamzandi.

There was a need to physically preserve the manuscripts, Camara said, but also to catalog these important materials to trace the origins of where they are found and to share information about them more widely.

“Who composed this poem? Where did it come from? Initially these poems were sung, but at one point they were written down, so we wanted to try to trace the authorship of the poems as best as we could,” Camara said.

On the ground in Senegal and Mali

Different members of the team made three trips to Senegal, beginning in 2019. (COVID-19 delayed the final trip in July 2021 for about a year). It was important to build trust with the family custodians of the manuscripts and to explain the value of the project, Camara said.

A view of Mount Tapa in southwestern Mali.

That’s where Bannen came in — she led workshops in Senegal to explain how careful the team would be with the manuscripts and to explain the value of them being made accessible online.

Bannen’s tools of the trade included a DSLR camera that would produce the quality of images the British Library needed, a tripod and a laptop. She has a master’s in fine arts in documentary photography from the University of Wales, Newport, and is now a graduate student in the UNC School of Information and Library Science.

Bannen praised her UNC library colleagues for helping her imagine how to do the work they do on a large scale in Wilson Library in a portable, scaled-down way.

“They showed me how to make book cradles out of cardboard, and I was armed with gloves and other tools that helped us minimize our handling of the manuscripts,” she said.

6,000 pages!

Collectively, the team digitized 6,000 pages of text, about 3,500 pages from Senegal and 2,500 from Mali. The materials will be archived in three digital repositories — the British Library’s Endangered Archives Program, University Libraries and the West African Research Center in Senegal. The project also received support from the AAAD department and the African Studies Center at UNC.

The team sets up equipment needed for digitization on a table at the West African Research Center.

The team split up tasks — photography, transcription of the materials, compiling metadata for each entry. They worked long hours and tried to maximize use of natural light in getting the best-quality images.

“Working at UNC with photos, rare books and manuscripts, I’ve had a lot of practice in creative problem-solving,” Bannen said in a 2020 University Libraries story on the trip.”

A journey to Pate Galo and the home of Mountaga Ba, one of the family custodians, resulted in an opportunity for the team to hear the poems being performed and Tijaniyya liturgies and chants being shared — a rewarding experience that brought the archival work they were doing to life.

“We saw these being expressed vividly when we were there,” Mwamzandi said.

The project was officially completed in March. But for Camara, the digitization of these important manuscripts is only the beginning. His plans include analyzing the cultural significance of these materials.

“I want to further explore how they are lived at home and in the diaspora and their religious and secular significance,” Camara said. “Because they are incorporated into popular music, you see the blurring of the boundaries of the secular and religious — and that speaks to the dynamics of modernization in Islamic culture.”

Learn more about the manuscripts and see images of them.

By Kim Spurr, College of Arts & Sciences

Posted from UNC College of Arts & Sciences